Joan of Arc was clearly a saint. She received visions, performed miracles, and laid down her life in the name of God.

But the cause to which she devoted her considerable spiritual powers was a strange one: getting Charles of Valois, the relatively inept Dauphin, crowned King of France.

At face value, this seems kind of stupid. We have all heard atheists mock pro athletes who thank God in their victorious post-game press conference. “Oh yeah, God has a favourite football team? What about last game, when you lost?” Joan, the thunderbolt of Orleans, seems like a similar case of dubious divine partisanship. What does God care which useless bastard happens to sit on a chair?

I think this speaks to something quite essential about Christianity. It is a religion uniquely concerned with history. The religions of the East prefer to escape into a personal and timeless enlightenment. Paganism is cyclical, like the seasons. But the Christian spirit is a change-making spirit, and it has given history a direction.

Islam has a concern with history at its core, too. But Islam is kind of like Marxism. It believes its ultimate triumph inevitable; it’s only a matter of time. Christianity says: all the time matters. Creation is now.

As for Joan, her mission was not merely to crown Charles, but in so doing, to save France from English rule. And this was verily a divine mission. In Christianity, all of creation has absolute significance. To save your country, you may as well be saving the world. Our modern conception of nation-states as arbitrary political entities would have been as alien to Joan as the idea that people are mere bags of chemical reactions. Her nation, she knew, had a part to play in the world to come. And God’s design would be hampered if one of His unique and beautiful daughters were to be oppressed by another.

Of course, this need not subdue our suspicions, for the countless instances in history where God has allowed just this to happen. England itself was conquered just a few centuries earlier. Things still turn out just fine; nations still take their shape, and contribute their voice to the chorus of humanity. But in the mean-time, it hurts.

~

War is hell, said General Sherman, and this statement’s precision has only grown. His audience, who still held vestigial notions of war as glorious, as potential gateway to maximum living, must have found it a striking and even perhaps an offensive claim. But since the Great War, we take it as a given.

Christ preached the Kingdom of Heaven, or at least this is the classic translation (something like “Reign of God” may be more accurate)—and there is an open question over whether it is our task to enact the Kingdom of Heaven, through doing God’s will in time; or whether God intends suddenly to establish it fully and finally in an apocalyptic intervention. The early Christians tended towards the latter view, and settled down into communes to love each other and pass the time before the Big Day. But after a few centuries, the tide changed, and the vision of progress took hold.

All agree that if the Kingdom of Heaven is something we are to build on Earth, it is yet unfinished. But probably we have already achieved Hell on Earth. Verdun, the meat grinder, its craters full of blood and shit and bodies and chemical rain, like Hell’s moon, with no heroes. Cambodia in Year Zero where all suspected nerds are exterminated and babies smashed against trees to save bullets. The Rape of Nanking where boys will be boys and corpses float down the Yangtze like fallen leaves. Sednaya’s torture chambers. Atlantic slave ships. Auschwitz, where work sets you free.

Man, we suffer a lot in civilization. And Christianity is all about suffering. Christianity is an interesting religion, because it is all about a lot of things. But, for my money, the two things that it is all about the most, are love and suffering.

We often hear the problem of pain or evil posed against Christianity. But Christianity itself comes out of this problem and is a response to it, and the testimony of ages seems to suggest it is a convincing response. Christ’s Passion and death on the cross represents infinite pain and infinite evil. He is utterly destroyed and humiliated, by forces infinitely beneath him: the bruised egos of some busybodies; the madness of the crowd; a mere physical empire. He takes it all on willingly, gracefully, courageously—he accepts it.

And then, on the third day, he rises!

So, in Christianity, suffering is a means to an end. Christ is revealed as God through his suffering on the cross, and his resurrection—together, they make a coherent story of union with God and ultimate triumph through suffering. Christ, as the Logos incarnate, is the perfect fractal of history itself, which is the realization of God’s love through the crucifixion and resurrection of man.

So, suffering is not bad. It is a gift. It is how God reveals himself. God reveals himself through joy as well. Both extremes are extremely divine. And they are of course connected.

In order to better understand the Christian view of suffering, we might contrast it with that other suffering-based religion: Buddhism.

Buddhism believes that life is suffering, because attachments lead to suffering, and life involves attachments. Buddha sought freedom from suffering through releasing attachments; neither seeking sensual pleasures nor reactively rejecting them; becoming indifferent. Christ’s achievement was much the opposite: absolute involvement with all creation.

Buddhism says (with modernity) that suffering is something to be escaped from, or at least minimized. Therefore, release attachments, for they are the cause of suffering. Christianity says (with romanticism) fuck that. Get in there. The ideal human being is absolutely attached to everyone and everything—and this is Christ.

In Christianity, suffering is always redemptive because it is always going somewhere. One might even say: in Buddhism, attachments lead to suffering; in Christianity, suffering leads to attachments. And attachments are the medium of love. So let us strive to strengthen them and extend our affinity with the whole unfolding story.

~

History is God’s revelation to the human heart, in time. It is a psychedelic trip, a poem, a lark, a work of art, a tragedy, a comedy, and above all, a romance. History is a love story.

Through our suffering in history, the upper echelon of love has grown in intensity and become available to all of humanity. Mystic love which may once have been the sole province of the poets and prophets, now becomes the norm.

We are talking about the love a man and woman have for each other, and the love they share for the child they came together to create.

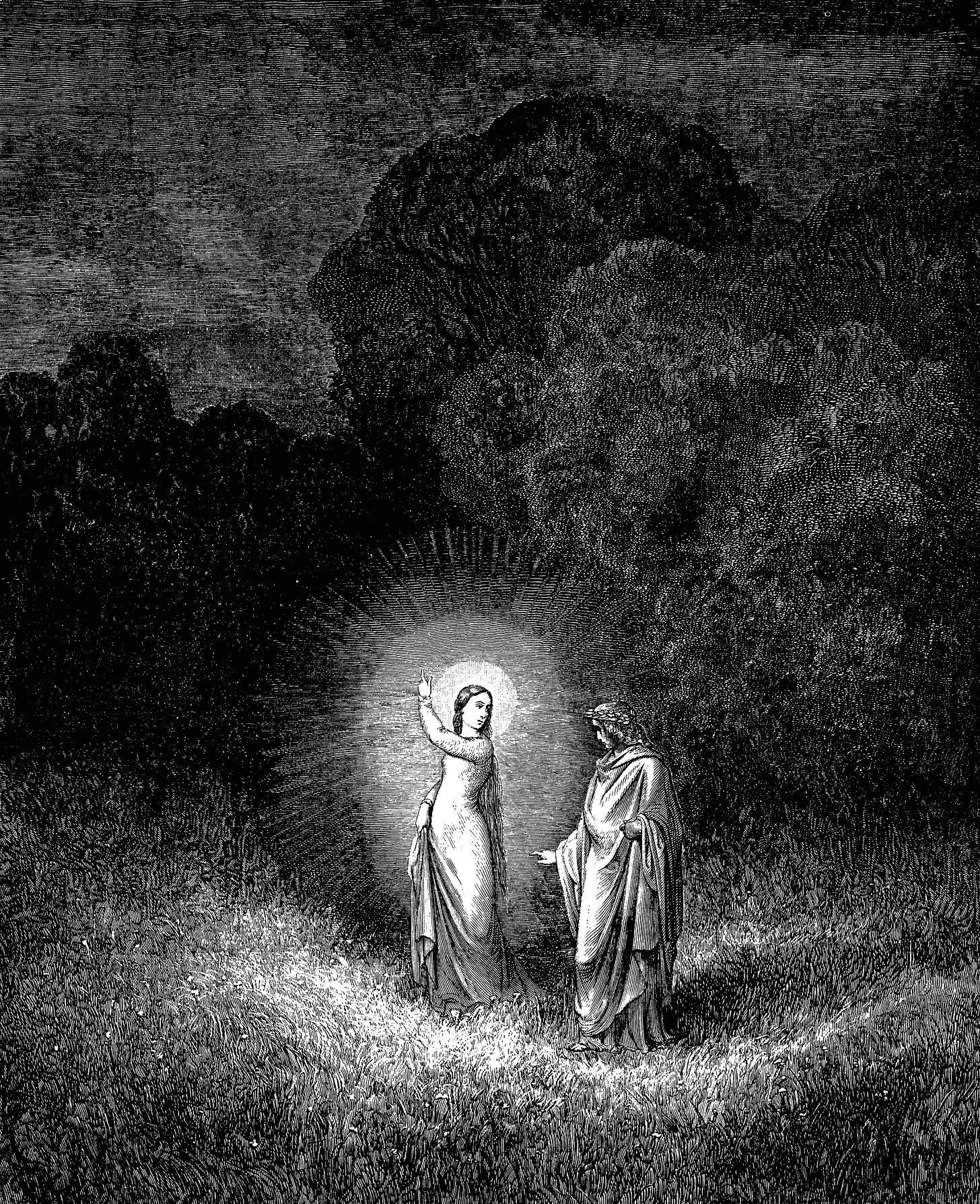

In a recent youtube video, I explored the emergence of the phenomenon of romantic love. For most of history, marriage was a practical business, with little call for affection, let alone transcendent significance. And hunter-gatherer tribes, whom I believe to be more or less representative of our original state, also lack the manic-obsessive tendency that moves Dante to write of Beatrice, his crush:

She is the sum of nature's universe.

To her perfection all of beauty tends.

This cosmic kind of love is novel, and somewhat freaky. So, where did it come from?

It seems to be something like a response to the fragmentation and isolation of life in civilization—particularly modernity.

Now, in the hunter-gatherer tribe, they have a lot of love for each other, and for the world around them. But this is exactly why they don’t display the same totalizing cosmic love for their partners and children. Their love is distributed across a wider field; their whole world is more or less lovable. We on the other hand find ourselves in a vast grotesque civilization where we make certain bonds of friendship and love, and all of our meaning must be concentrated on these. It is our loneliness that intensifies our love for a few. And they literally come to mean the world to us.

For the last few centuries, most people have continued to enjoy some degree of tribal-type communal ecosystem, whether that’s a village or a big extended family with an awesome Nonna and a couple hundred cousins. Only the particularly unlucky, cerebral, or both, experienced the loneliness which now is utterly ubiquitous. Dante is the perfect example—he spent most of his life in exile, and he was insanely brilliant. This was, as ever, a recipe for a serious case of the blues. Nowadays, the most normal guy in the world might be as lonely as Dante.

We may be tempted, then, to view the total love of the poets as a maladaptation—an unhealthy response to an unhealthy culture. There is certainly some truth in this. We have all witnessed a bad romance. But through my investigation of this question, I have come to think that total love is not merely a coping mechanism. I think it’s alchemy. Not an illusion, but an unveiling. This love, I feel, is part of our destiny; our story as a species. We were bound to grow into it.

In order to discover this mystical love for another, it was necessary for us to become lonely.

Loneliness is the greatest pain for a social animal. We are meant to be together; our bodies crave the other’s rhythms. Our loneliness is therefore the most cutting-edge form of agony. For some, it turns every day into an internal Verdun. Almost a million people a year kill themselves, in despair. This despair is no chemical imbalance—it is loneliness; which, when it is total, is Hell on Earth. Teenage girls cutting themselves and starving themselves striving to be as empty as they feel. Incels letting loose on their community in an ecstasy of evil. Boozed men numb and tranced by the hum of the fridge and the TV playing to no one. Guys in solitary confinement forgetting their mother’s face.

Loneliness drives people mad. And romance is distinctly a kind of madness.

To become as individuals is the greatest trauma yet visited on an essentially tribal humanity. Yet, this trial has yielded a great treasure: the ability to love other individuals with the same force with which we used to love the whole world.

The crucible of civilization has crushed us into this diamond. We now reflect the love of God, more perfectly.

A new form of love has come on the scene. I believe it is a new threshold of God’s revelation to humanity in history. According to Christianity, God reveals himself through suffering which leads to joy. The loneliness which leads to finding your one true love happens to fit this pattern exactly, and it is quickly becoming ubiquitous across the species. I think it is more than mere culture. I think culture merely reflects spiritual trends. Horizons of mystical union begin to make themselves known, and are identified first by the poets; they slowly become known to all until they are so obvious as to be invisible. Then a new horizon appears.

May we have eyes to see it, and the courage to seek it! Amen.