I think this is a mental picture to which I will return often in my dealings with heathens—because it works for me, and I am the heathen.

Many people believe in “something.” This is the first principle referred to in this article’s title, and I will take the further liberty of identifying this “something” as some kind of “infinite.” Naturally there is much confusion between the mathematical and metaphysical infinite here; when people use the term in this way they are almost always referring to the latter, but the term’s ostensibly mathematical nature seems to lend them permission; it feels somehow more scientific and rational than “God.” Likewise with the term “the universe”—very rarely are they referring to the indifferent God of Spinoza, but to a larger conscious order which encompasses them, created them, and is helping them on their way, rather like a friend or parent, only infinite and incomprehensible. Which they elect to call “the universe,” since “God” is passé.

Very well. Let us take as our starting point the idea of the “infinite” as the origin and ultimate essence of things.

We are all familiar with the image of a monkey at a typewriter infinitely typing random keys. He will inevitably produce all possible combinations, including the complete works of Shakespeare, along with infinitely many equally compelling and novel works of literature. It will take him a very long time, in fact an infinitely long time, but that is exactly what we give him.

Certain moderns, clutching stubbornly to the corpse of reductionist materialism, maintain that ultimate reality—the “multiverse”—is a kind of infinite possibility space. It’s infinite so in it everything happens; all possible universes exist. This is their answer to the “fine-tuning” argument for God’s existence, which says: all the cosmological constants and forces and laws are balanced just right for stars and planets and life to emerge. Tweak them a hair and the whole thing would never be able to produce organic order—it would either be scattered gas or dense black-hole-y soup. We find ourselves in the Goldilocks zone of all Goldilocks zones: matter can meet and mingle just right. What are the odds that this would be so, if there were no creative agency behind the universe? Well, the odds would be 100% if all possible rulesets exist in their own universe, and the “anthropic principle” points out that only those universes capable of producing conscious observers would ever be observed. So from the perspective of the creatures in question, it seems infinitely unlikely that the universe should be balanced just so. But they can only be in such a universe, in the first place. The physicist Max Tegmark is a particularly inventive exponent of this view. He says “that all possible mathematical structures exist as physically real universes.”

There is no particular reason to believe that a true metaphysical infinite would be limited to expressing itself in the form of random parameters for physical universes. Believing this is no more and no less rational than believing the ultimate reality is literally a monkey at a typewriter banging out mostly nonsense with the occasional novel. Let me clarify what I mean. Saying that everything is “mathematical objects” is a metaphor, just like saying that everything is “written words.” Both statements are in a sense true, as both languages—mathematical formulae and phonetic text—are expressions of the divine Logos. Both can channel it, express it, reveal it; neither can contain it. Tegmark famously predicted that by 2050 you would be able to get the formula for the unified law of the universe printed on a T-shirt. This is precisely as likely as summing it all up in a line of poetry. It is not reducible to formulae, and it is not a product of formulae, any more than it is a product of sentences.1

A true infinite would contain all—not just all of one type of thing. Not just all strings of Latin characters or all mathematical constructs, but all.

A true infinite would contain an infinite consciousness.2 (In fact, now that I think about it, this ought to apply even if you believe in reductionism, since you are obliged to believe that consciousness itself is a “mathematical object”—and math is easily weird enough that an infinite field of all the mathematical objects ought to contain an infinite and freaky and fractal version of this particular object, so infinite and freaky and fractal perhaps as to be entangled with all other objects…)

And an infinite consciousness ought in turn to contain an infinite consciousness concerned with creating creatures and universes in which for them to live and move and have their being.

Which in turn ought to contain an infinite consciousness—it’s infinite consciousness all the way down—which happens to be a Person. And it is surely in this aspect that He would be most likely to reveal Himself to us, if He cared to do so. And the evidence suggests that He does care.

Well, this line of thinking isn’t really how I came to (mostly) believe in the Trinity. The reason why I like the Trinity idea enough to believe in it is because it feels true that the infinite absolute ought to be a dynamic communion—communication! in love!—rather than a static self-satisfaction.

One of my favourite books is Sadhana: The Realization of Life by Rabindranath Tagore. In truth I have never read the whole thing all the way through, though as McLuhan says,

The Hebrew and Eastern mode of thought tackles problem and resolution at the outset of a discussion, in a way typical of oral societies in general. The entire message is then traced and retraced, again and again on the rounds of a concentric spiral with seeming redundancy. One can stop anywhere after the first few sentences and have the full message, if one is prepared to “dig” it.

I stopped after the first chapter of Tagore’s Sadhana (the chapters were originally standalone speeches), and though I have grazed throughout the slim book, it is this chapter, entitled “The Relation of the Individual to the Universe” that in my Lean I Might period I thoroughly dug. It was what I was talking about!3

I still feel that these pages are the best encapsulation of Eastern monistic mysticism, which we might consider Pure Metaphysics. The one universal infinite eternal divine manifesting in infinite diverse fractal forms in paradoxical motion and stillness, etc.

The great fact is that we are in harmony with nature; that man can think because his thoughts are in harmony with things; that he can use the forces of nature for his own purpose only because his power is in harmony with the power which is universal, and that in the long run his purpose never can knock against the purpose which works through nature…

The fundamental unity of creation was not simply a philosophical speculation for India; it was her life-object to realise this great harmony in feeling and in action. With mediation and service, with a regulation of life, she cultivated her consciousness in such a way that everything had a spiritual meaning to her. The earth, water and light, fruits and flowers, to her were not merely physical phenomena to be turned to use and then left aside. They were necessary to her in the attainment of her ideal of perfection, as every note is necessary to the completeness of the symphony. India intuitively felt that the essential fact of this world has a vital meaning for us; we have to be fully alive to it and establish a conscious relation with it, not merely impelled by scientific curiosity or greed of material advantage, but realising it in the spirit of sympathy, with a large feeling of joy and peace.

The man of science knows, in one aspect, that the world is not merely what it appears to be to our senses; he knows that earth and water are really the play of forces that manifest themselves to us as earth and water - how, we can but partially apprehend. Likewise the man who has his spiritual eyes open knows that the ultimate truth about earth and water lies in our apprehension of the eternal will which works in time and takes shape in the forces we realise under those aspects. This is not mere knowledge, as science is, but it is a preception of the soul by the soul. This does not lead us to power, as knowledge does, but it gives us joy, which is the product of the union of kindred things. The man, whose acquaintance with the world does not lead him deeper than science leads him, will never understand what it is that the man with the spiritual vision finds in these natural phenomena. The water does not merely cleanse his limbs, but it purifies his heart; for it touches his soul. The earth does not merely hold his body, but it gladdens his mind; for its contact is more than a physical contact - it is a living presence.

When a man does not realise his kinship with the world, he lives in a prison-house whose walls are alien to him. When he meets the eternal spirit in all objects, then is he emancipated, for then he discovers the fullest significance of the world into which he is born; then he finds himself in perfect truth, and his harmony with the all is established. In India men are enjoined to be fully awake to the fact that they are in the closest relation to things around them, body and soul, and that they are to hail the morning sun, the flowing water, the fruitful earth, as the manifestation of the same living truth which holds them in its embrace. Thus the text of our everyday meditation is the Gayatri, a verse which is considered to be the epitome of all the Vedas. By its help we try to realise the essential unity of the world with the conscious soul of man; we learn to perceive the unity held together by the one Eternal Spirit, whose power creates the earth, the sky, and the stars, and at the same time irradiates our minds with the light of a consciousness that moves and exists in unbroken continuity with the outer world…

The Upanishad says,

Yaçchāyamasminnākāçē tējōmayō'mritamayah purushah sarvānubhūh

The being who is in his essence the light and life of all, who is world-conscious, is Brahma. To feel all, to be conscious of everything, is his spirit. We are immersed in his consciousness body and soul. It is through his consciousness that the sun attracts the earth; it is through his consciousness that the light-waves are being transmitted from planet to planet.

Yaçchāyamasminnātmani tējōmayō'mritamayah purushah sarvānubhūh

Not only in space, but this light and life, this all-feeling being is in our souls. He is all-conscious in space, or the world of extension; and he is all-conscious in soul, or the world of intension. Thus to attain our world-consciousness, we have to unite our feeling with this all-pervasive infinite feeling. In fact, the only true human progress is coincident with this widening of the range of feeling. All our poetry, philosophy, science, art and religion are serving to extend the scope of our consciousness towards higher and larger spheres. Man does not acquire rights through occupation of larger space, nor through external conduct, but his rights extend only so far as he is real, and his reality is measured by the scope of his consciousness.

Well, this is all true, and good, and beautiful, and I love it and it is still foundational to my worldview. But it is not the full truth. It is too simple.

My own dissatisfaction with Pure Metaphysics began over 2 years ago. I wrote this piece called Chocolate Eggs at the time, which is mostly quite bad, but interesting for a few reasons: time capsule to how much worse chat used to be, and a certain stage of my own grapplings—with many of our current themes in a less mature form. Read it here, if you like.

The modern belief that Math and Physics are somehow God carries more than a shade of what Christianity believes about Christ, the eternal Son, identified by St. John as the Logos: both the organizing principle and meaning of the universe. The Greek λογος is translated as “word,” which is right—the universe is made of language; this life is a thing of communication; and Christ is what is being communicated. But λογος also means: reason, principle, pattern. It had held these meanings (along with the concept of “meaning” itself) for centuries by the time the Gospels were written.

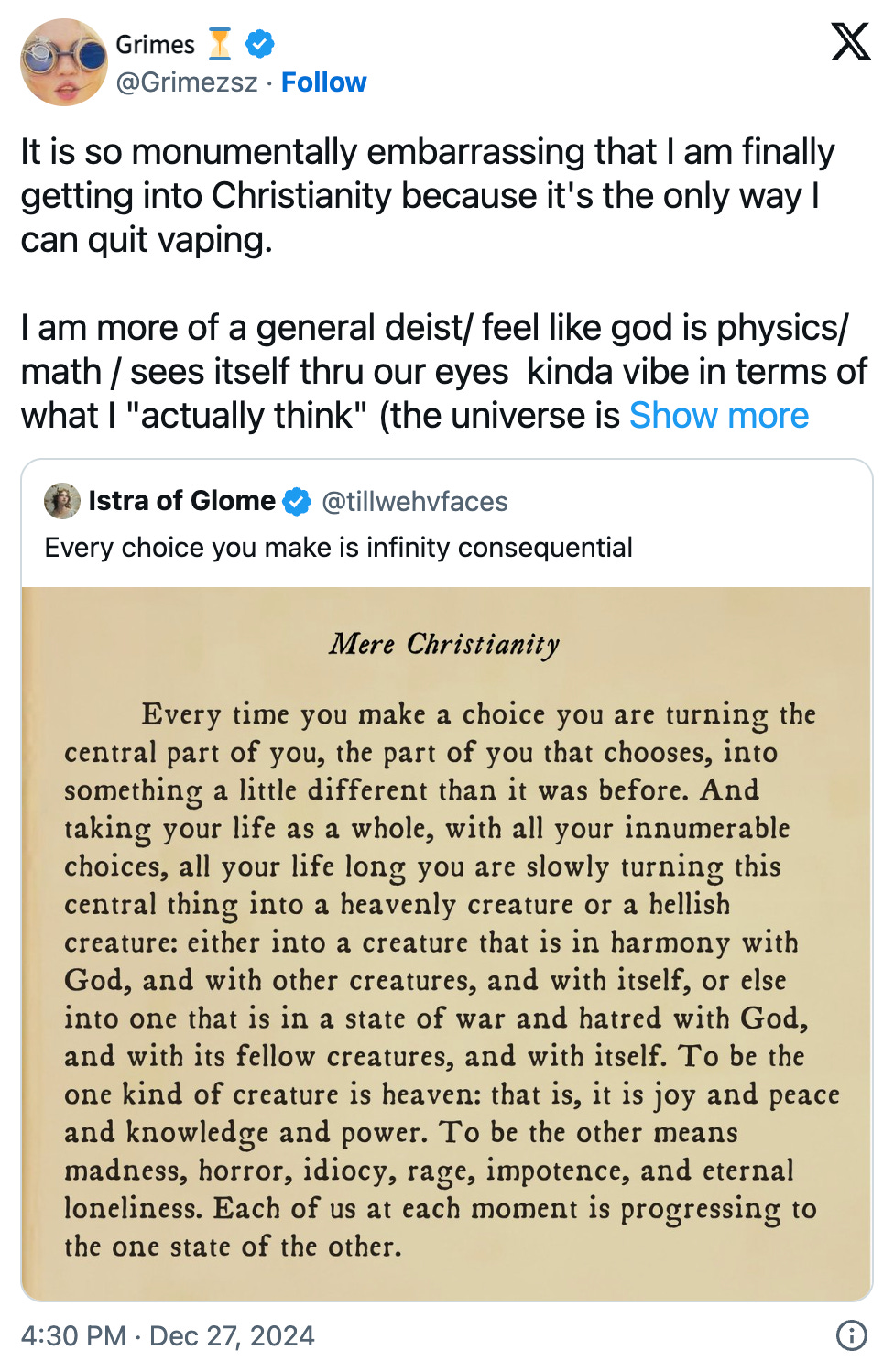

The vague modern metaphysics (and its total inadequacy) found adequate expression in the following Christmastime tweet of Grimes, occasioned by a C.S. Lewis quote:

Funnily enough, Lewis talks about this sort of thing as well, in Mere Christianity:

Dozens of people go to [Our Lord] to be cured of some one particular sin which they are ashamed of (like masturbation or physical cowardice) or which is obviously spoiling daily life (like bad temper or drunkenness). Well, He will cure it all right: but He will not stop there. That may be all you asked; but if once you call Him in, He will give you the full treatment.

That is why He warned people to “count the cost” before becoming Christians. “Make no mistake,” He says, “if you let me, I will make you perfect. The moment you put yourself in My hands, that is what you are in for. Nothing less, or other, than that. You have free will, and if you choose, you can push Me away. But if you do not push Me away, understand that I am going to see this job through. Whatever suffering it may cost you in your earthly life, whatever inconceivable purification it may cost you after death, whatever it costs Me, I will never rest, nor let you rest, until you are literally perfect — until my Father can say without reservation that He is well pleased with you, as He said He was well pleased with me. This I can do and will do. But I will not do anything less.”

And yet — this is the other and equally important side of it — this Helper who will, in the long run, be satisfied with nothing less than absolute perfection, will also be delighted with the first feeble, stumbling effort you make tomorrow to do the simplest duty. As a great Christian writer (George MacDonald) pointed out, every father is pleased at the baby's first attempt to walk: no father would be satisfied with anything less than a firm, free, manly walk in a grown-up son. In the same way, he said, “God is easy to please, but hard to satisfy.”

The practical upshot is this. On the one hand, God's demand for perfection need not discourage you in the least in your present attempts to be good, or even in your present failures. Each time you fall He will pick you up again. And He knows perfectly well that your own efforts are never going to bring you anywhere near perfection. On the other hand, you must realise from the outset that the goal towards which He is beginning to guide you is absolute perfection; and no power in the whole universe, except you yourself, can prevent Him from taking you to that goal. That is what you are in for. And it is very important to realise that. If we do not, then we are very likely to start pulling back and resisting Him after a certain point. I think that many of us, when Christ has enabled us to overcome one or two sins that were an obvious nuisance, are inclined to feel (though we do not out it into words) that we are now good enough. He has done all we wanted Him to do, and we should be obliged if He would now leave us alone. As we say “I never expected to be a saint, I only wanted to be a decent ordinary chap.” And we imagine when we say this that we are being humble.

But this is the fatal mistake. Of course we never wanted, and never asked, to be made into the sort of creatures He is going to make us into. But the question is not what we intended ourselves to be, but what He intended us to be when He made us. He is the inventor, we are only the machine. He is the painter, we are only the picture. How should we know what He means us to be like? You see, He has already made us something very different from what we were. Long ago, before we were born, when we were inside our mothers' bodies, we passed through various stages. We were once rather like vegetables, and once rather like fish; it was only at a later stage that we became like human babies. And if we had been conscious at those earlier stages, I daresay we should have been quite contented to stay as vegetables or fish — should not have wanted to be made into babies. But all the time He knew His plan for us and was determined to carry it out. Something the same is now happening at a higher level. We may be content to remain what we call “ordinary people”: but He is determined to carry out a quite different plan. To shrink back from that plan is not humility; it is laziness and cowardice. To submit to it is not conceit or megalomania; it is obedience...

The command Be ye perfect is not idealistic gas. Nor is it a command to do the impossible. He is going to make us into creatures that can obey that command. He said (in the Bible) that we were "gods" and He is going to make good His words. If we let Him — for we can prevent Him, if we choose — He will make the feeblest and filthiest of us into a god or goddess, a dazzling, radiant, immortal creature, pulsating all through with such energy and joy and wisdom and love as we cannot now imagine, a bright stainless mirror which reflects back to God perfectly (though, of course, on a smaller scale) His own boundless power and delight and goodness. The process will be long and in parts very painful; but that is what we are in for. Nothing less. He meant what He said.

So, Grimes is in for a heck of a lot more than “not vaping.” But this has all been a digression! I couldn’t help myself.4

To briefly conclude: it seems that there exists some kind of infinite source of all being, life, and consciousness; with which we are in constant contact. The nature of this contact seems to be more like a personal relationship than anything else.

The single individual as the particular stands in an absolute relation to the absolute.

- Kierkegaard

And is a living relationship: paradoxical and ever-evolving. The absolute is not only the infinite source of energy and organizing principle behind the universe, but also a Person who reaches out to us in love. Grant that it is infinite, and it must necessarily contain such a thing.

For what it’s worth, I’m 100% sure that it’s not reducible to formulae but only 95% sure that my analogy is exactly right.

Strictly speaking, the concept of “consciousness” is just as primary as the concept of “infinite,” as God is both, but here it is convenient to argue that the one follows from the other.